Amid war, sanctions and looming collapse, Moscow says Russian Arctic shipping will thrive

A new government plan for the Northern Sea Route includes unprecedented investments in new ships, infrastructure and natural resource development. "It is nothing but a play staged by state officials," a leading Russian expert says about the document.

The development plan that was adopted by the federal government on the 4th of August has grand ambitions for the Russian Arctic. Over the period until 2035, a total of 1,8 trillion rubles (€30,1 billion) is to be invested in 152 regional projects.

Among them is the building of 153 new ice-class ships, including ten icebreakers, twelve new seaports, twelve satellites, thirteen helicopters, several hospitals and search and rescue units.

All of this will allow Russia to transport up to 100 million tons of goods per year by 2025 and 200 million tons by 2030, the federal Ministry of the Far East and Arctic informs.

The adoption of the document did not come easy. Reportedly, Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Trutnev locked all involved officials into a small and uncomfortable meeting rom on a top floor in the government building and refused to let people leave until the document was approved by everyone.

The plan comes as Russia spends major parts of its state treasury on the war against Ukraine and international sanctions cripple key sectors of its economy.

Nonetheless, the Russian government argues that the Northern Sea Route is a much-needed priority.

“This is a reliable maritime seaway, widely needed by businesses and of course by the people that live in the Arctic and the Far East,” Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin underlined in a presentation.

“And it is fully located in our territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zone, which is of key importance in a time of external pressure from sanctions and when logistics chains for delivery of goods are disrupted,” he added.

The new plan comes after President Vladimir Putin in April this year called for an acceleration of current and future projects in the region.

But far from everyone has faith in the projects.

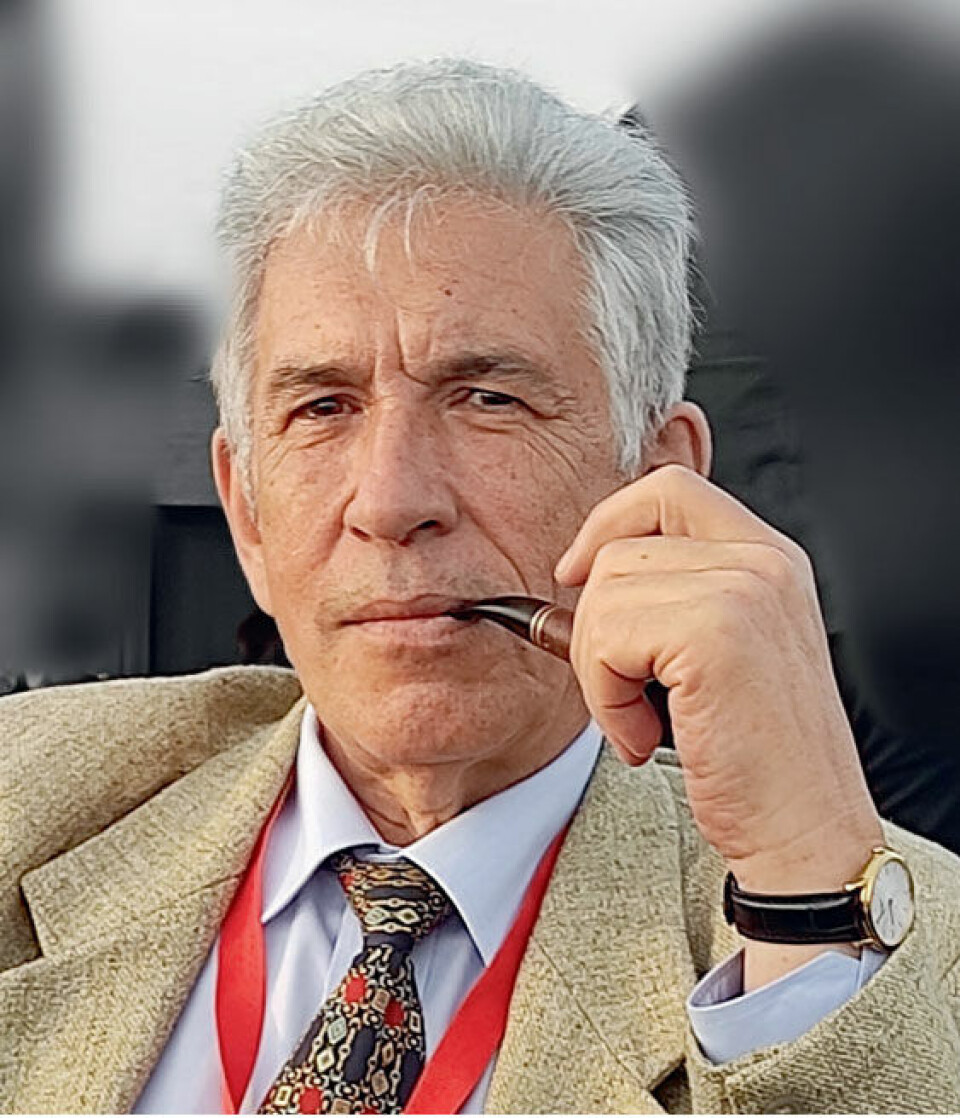

Leader of consultancy company Gecon Mikhail Grigoriev says he has been skeptical towards the official government policy at least since 2018 when Vladimir Putin requested that annual goods volumes on the route reach 80 million tons by 2024.

According to Grigoriev, it is not clear from where the vast goods volumes will come.

“I know well the basic federal objectives for goods traffic, and I do not see these kind of volumes,” he says in a lengthy interview to news journal Korabel.

“I get the impression that this is nothing but a play staged by state officials,” he underlines.

And the war has made everything much more difficult. “The feeling among international shippers and traders is that everything that goes through Russia now is like acid,” he says.

Grigoriev is a widely respected veteran in Russian Arctic developments and has over the last two decades worked comprehensively with issues of transportation and natural resources extraction in the region.

He was skeptical to the plans of Dmitry Bosov and his company Vostokugol to extract more than 30 million tons of coal from the Taymyr Peninsula and export it through Arctic waters. Similarly he is today skeptical to the plans of Rosneft to produce more than 100 million tons of oil per year as part of its project Vostok Oil.

Rosneft will hardly be able to build a sufficient number of ice-class tankers to reach its much-announced plans, he argues.

He has a similarly lack of confidence in Novatek and its plans for the Arctic LNG 2. According to Grigoriev, the outlined LNG production volumes are far too optimistic. The second and third trains in the project are likely to face delays as foreign technology need to be replaced by Russian. Operational adjustments are needed, and this will require both time and money, he explains.

Mikhail Grigoriev is far from the only expert questioning the credibility of plans for the Northern Sea Route.

U.S researcher and former Coast Guard officer Lawson W. Brigham has great doubts that the NSR ever will become a significant international trade route for shipping and also argues that ongoing energy transition might ultimately reduce demand for Russia’s commodities from the region.

Also Norwegian researcher Arild Moe has doubts about the Russian Arctic ambitions.

According to Moe, the realism of Russia’s plans could be questioned already in 2020 when a Strategy document for the NSR was issued.

“Neither then, nor now is the plan fully financed. It requires very substantial investment from commercial actors,” the researcher from the Fridtjof Nansen Institute says to the Barents Observer.

“The government pretends that nothing has happened that could change the outlook. But obviously, factors beyond the government’s control are impacting developments. They include technology sanctions that will delay projects, particularly LNG, but also limitations on market access,” he underlines and adds that investment risks in the Russian Arctic now are regarded as higher than before.

That includes investments in ships specially designed for operations on the Northern Sea Route, Moe explains.

Meanwhile, the ice-free season is soon approaching in the area. Maps from the Russian Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute show that large parts of the route by Mid-August had open waters. A rapidly increasing number of ships are shuttling through the area. But this year, they are almost exclusively Russian.

According to data from the Northern Sea Route Administration, a unit operated by nuclear power company Rosatom, no European, American or Chinese ship has this year applied for entry into the area.